With advances in technique and supportive care, bone marrow transplant (BMT) patients have a longer life expectancy now than when BMT was first performed more than 40 years ago. Despite much higher mortality rates than the general population, up to 80% of BMT patients who survive 5 years posttransplantation will be alive 20 years posttransplantation.1 However, patients who live longer can be at higher risk for complications, in part because of changes in their body’s immune system.2 One of these concerns is the loss of immunity that was previously achieved through vaccination. To regain immunity to vaccine-preventable diseases, including measles, mumps, hepatitis, and diphtheria, patients need to be revaccinated following BMT.3

In addition, BMT patients may require medications to treat chronic complications from their transplantation. It is well documented that medication discrepancies are common in many patients.4,5 BMT patients may be at a higher risk for medication discrepancies compared with the general population, because they are frequently changing medications posttransplantation and have frequent transitions in their care between inpatient and outpatient settings.6 Pharmacists are the ideal healthcare professionals to provide medication reconciliation and management services.7,8

At St. Luke’s Mountain States Tumor Institute (MSTI) in Boise, ID, patients are asked to stay in the infusion area for approximately 30 minutes following vaccinations to monitor for adverse immunologic reactions from the vaccines. This is an ideal time for pharmacists to meet with patients and perform medication reconciliation or medication therapy management.

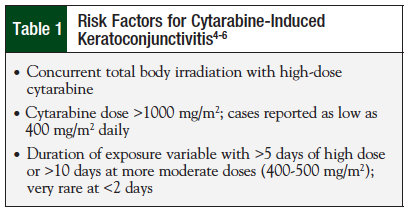

The catalyst for this project at St. Luke’s MSTI was that, prior to its initiation, pharmacy had little involvement in the post-BMT vaccination process. This had led to prolonged wait times for patients, and could potentially lead to errors in administration, including the wrong vaccine or a vaccine being given at the incorrect time following transplant. Table 1 includes times when vaccinations should be given, from the current BMT protocol for autologous transplants. St. Luke’s MSTI is a regional cancer center that performs 15 to 25 autologous transplants annually and manages patients with postallogeneic transplantation. MSTI has 5 locations, 6 BMT physicians, and 2 nurse practitioners. BMTs are only performed at the Boise location but long-term follow-up can take place at any of the 5 practice sites. The pilot project was implemented to improve patient care by decreasing wait times and providing consistency throughout the post-BMT process. The project also attempted to determine if it could be cost-effective to have a pharmacist manage all BMT vaccines.

To our knowledge, this is the first report addressing the role of a pharmacist in the posttransplant vaccination process.

Methods

The purpose of this pilot project was to standardize the post-BMT vaccination process and to improve patient care by reducing wait times and avoiding potential vaccine or medication-related errors. The project was also designed to determine the feasibility of having a pharmacist available to manage vaccinations for post-BMT patients.

A pilot process improvement project was conducted from January through April 2014. We evaluated pharmacist involvement in the BMT vaccination process with concurrent medication therapy management for BMT patients. The pilot was conducted at St. Luke’s MSTI in Boise, ID, where >50% of BMT patients received their vaccinations. Because this was a pilot project, all patients who were receiving their post-BMT vaccines were included in the analysis. Data collected included patient demographics, vaccination costs, and changes made to medication lists following pharmacist interview. Data were collected at the time of patient interaction. All changes were updated in the patient’s electronic medical record, as well as on a data collection sheet used by the study investigators.

To include all BMT patients in the pilot project, the primary investigator obtained a list of all BMT patients and determined when they would each be scheduled for their posttransplant vaccines, based on our institution’s vaccination policy (ie, 6, 12, and 24 months posttransplant for autologous transplants, varied based on outside institutions for allogeneic transplants; see Table 1). A pharmacist contacted the patient the day before his or her appointment to let them know that they would be assisting with the vaccination process, be available to review their medication list, and answer any questions they may have about their medications. The patient was encouraged to either bring their medications or an updated medication list to the appointment so that a medication reconciliation session could be completed.

The day of the appointment, the pharmacist would ensure that the correct vaccines were ordered by their oncologist. The vaccines would then be entered into the pharmacy system so that they would be ready when the patient showed up at the infusion center. An immunization-certified pharmacist assisted with the vaccination process by administering the vaccines in conjunction with the infusion center nurses. Following vaccination, medication reconciliation was performed with recommendations provided to the oncologist, and updates made to the patient’s chart.

Results

During the pilot period, 21 patients were vaccinated across the 5 St. Luke’s MSTI sites. Eight patients were vaccinated outside of Boise, and 1 patient was an add-on vaccination and was not included in the pilot. The total number of patients included in the pilot was 12. The median age was 59 years (30-72 years), 67% (n = 8) of the patients were women, and the average number of medications per patient was 8.9. Overall, 7 patients had myeloma, 3 patients had non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and 2 patients had acute myeloid leukemia.

Cost Considerations

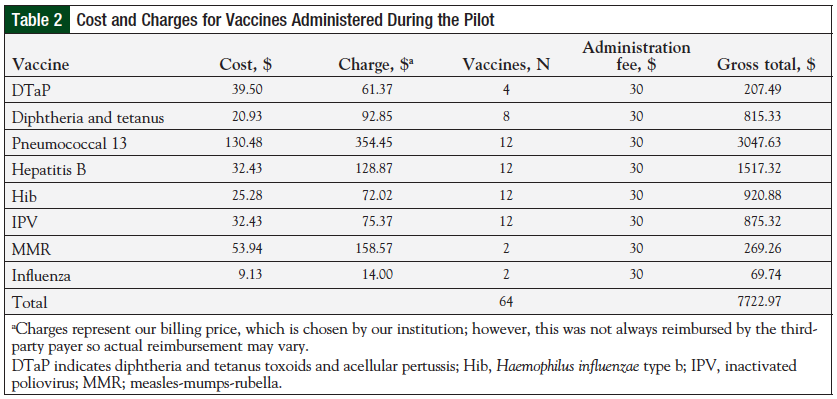

A total of 64 vaccines were administered during the pilot. The costs and list of the different vaccines administered are shown in Table 2. The total estimated gross revenue for 12 patients was approximately $7700. Because of variability in reimbursements among third-party payers, it is difficult to determine the actual revenue attributed to this pilot.

Medication Reconciliation

Eight (67%) of the 12 patients had at least 1 change made to their medication list based on the pharmacist review. A total of 23 changes were made—12 medications added to medication lists, 10 medications removed or adjusted, and 1 therapeutic recommendation made to discontinue a proton pump inhibitor. In addition, pharmacists provided education on vaccines and prescription medications, recommendations related to over-the-counter and herbal products, and resources and education about the disposal of unneeded oral chemotherapy medications. Although not all of these services were used by all patients, a pharmacist was available to answer questions and facilitate discussions.

Discussion

Having a pharmacist available to oversee the post-BMT vaccination process ensured that the vaccinations and staff were prepared in anticipation of a patient’s arrival. Although no objective data were obtained regarding patient wait times before and after the pilot, feedback from both nursing and pharmacy staff indicated that the vaccination process was smoother and more efficient following the initiation of the project.

Based on our findings, the gross revenue from this pharmacist-involved vaccine service would be approximately $35,000 annually, which is far below the average pharmacist salary.9 This figure only represents the costs and charges for the vaccines and administration extrapolated from the 4-month pilot. Costs associated with staff time, infusion center charges, and other costs were not considered. Despite this low annual revenue, these findings may be able to contribute to the funding for a full-time BMT pharmacist position at St. Luke’s MSTI in the future.

One aspect that was not specifically addressed in this pilot was how to manage the vaccines at the other St. Luke’s MSTI sites. A total of 8 patients were vaccinated at the other 4 St. Luke’s MSTI locations. A problem sometimes faced by other St. Luke’s MSTI sites is that each site must purchase an entire box of each vaccine in order to vaccinate a patient. The site may end up using only 1 to 3 vaccines before expiration, then disposing of the remainder—leading to increased cost because of waste. This could be an area of future focus and possible cost-savings.

In addition to the information obtained from the vaccination pilot, it was discovered that 67% of the BMT patients potentially have medication errors on their medication lists. This is a small subset of the patient load at St. Luke’s MSTI, but other sources have suggested similar problems in patients with cancer in general.10 The medication reconciliation service could potentially be expanded to all patients at St. Luke’s MSTI regardless of cancer type or procedure because of the potential for decreasing medication-related errors.

Conclusion

This pilot showed that by having a pharmacist involved in the post-BMT vaccination process, patients were able to receive better overall care, and demonstrated an additional area in which pharmacists can contribute to the healthcare team. The standardization of the vaccination process helped to decrease potential errors caused by inconsistencies. The medication reconciliation service identified that several of our patients had medication discrepancies, which we were able to correct. These discrepancies were identified by pharmacists despite each patient having a medication reconciliation performed by a nurse or medical assistant at each visit. This further demonstrates the value of the pharmacist in the medication reconciliation/management process. Correcting these discrepancies could potentially reduce medication-related errors in the future.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Mancini is on the Speaker’s Bureau of Millennium Pharmaceuticals. Dr Pence reported no conflicts of interest.

References

- Martin PJ, Counts GW Jr, Appelbaum FR, et al. Life expectancy in patients surviving more than 5 years after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28:1011-1016.

- Majhail NS, Rizzo JD, Lee SJ, et al. Recommended screening and preventive practices for long-term survivors after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:348-371.

- Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: a global perspective. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44:453-558.

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Institute of Medicine. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. 1st ed. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2000.

- Knez L, Suskovic S, Rezonja R, et al. The need for medication reconciliation: a cross-sectional observational study in adult patients. Respir Med. 2011;105(suppl 1): S60-S66.

- Ho L, Akada K, Messner H, et al. Pharmacist’s role in improving medication safety for patients in an allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant ambulatory clinic. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2013;66:110-117.

- Conklin JR, Togami JC, Burnett A, et al. Care transitions service: a pharmacy-driven program for medication reconciliation through the continuum of care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71:802-810.

- Pence S, Shipley J. Medication reconciliation in the ED: the Licking Memorial Hospital experience. Ohio Pharmacist. 2012 May:18-19.

- US Department of Labor. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Pharmacists. www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/pharmacists.htm. Published January 8, 2014. Accessed February 12, 2015.

- Mancini R. Implementing a standardized pharmacist assessment and evaluating the role of a pharmacist in a multidisciplinary supportive oncology clinic. J Support Oncol. 2012;10:99-106.