Nausea and vomiting are common side effects of anticancer agents and can have significant negative impact on patients’ quality of life and on their ability to tolerate and adhere to cancer treatment.1 “Despite advances in the prevention and management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV), these side effects remain among the most distressing for patients,” Rao and Faso noted in their review of CINV prevention and management.1

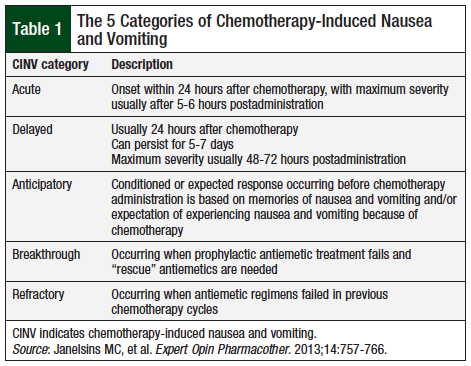

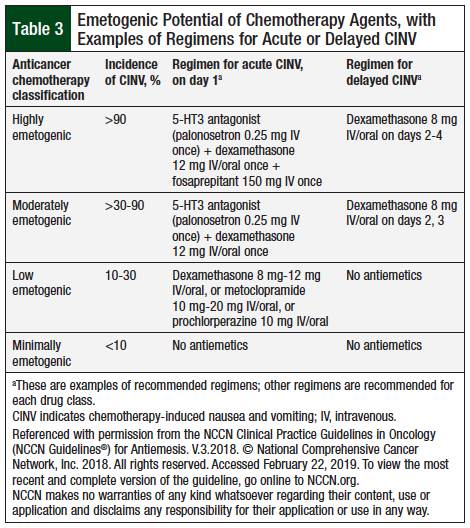

CINV is among the most worrisome side effects of chemotherapy agents, and despite advances in chemotherapy and in antinausea therapies, CINV continues to be a common side effect of treatment. Nausea and vomiting can occur shortly after the administration of chemotherapy, or it may be delayed; it may last for several days after treatment. The reported incidence of CINV varies widely, from less than 10% for minimally emetogenic agents to more than 90% for highly emetogenic agents.2 As shown in Table 1, CINV has been classified into 5 categories.3

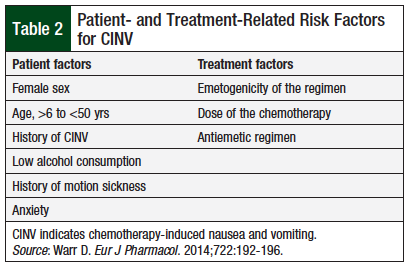

The risk factors for CINV can be classified into patient-related and treatment-related factors, as summarized in Table 2.4

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) has classified the anticancer agents into 4 categories, based on the emetogenic potential of the intravenous (IV) agents (Table 3).5 Table 3 provides an example of an NCCN-recommended regimen of antiemetic drugs for each of these 4 drug classes.

Olanzapine is an atypical antipsychotic drug that blocks many neurotransmitter receptors, including dopaminergic, serotonergic, muscarinic, and histamine H1 receptors. It has higher affinity for serotonin or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptors than dopamine D2 receptors. Olanzapine is used for the treatment of schizophrenia and delirium. Olanzapine’s efficacy in treating nausea and emesis refractory to standard antiemetic drugs is mediated through multiple receptors, particularly at the D2 receptors, 5-HT2c receptors, and 5-HT3 receptors.6

Method

We performed a literature review by searching the MEDLINE database through PubMed for relevant articles, including meta-analyses, systematic reviews, review articles, randomized and nonrandomized clinical trials, as well as case reports. Our search keywords included olanzapine, CINV, and antiemetics and their Medical Subject Heading terms.

In addition, a manual search was performed through major journals for articles referenced in journals located through PubMed. We also performed a literature search in the Cochrane Library Database to identify any published systematic reviews related to this subject.

All relevant publications were included in the research results pertaining to olanzapine use for CINV, including clinical guidelines, systematic reviews, clinical studies, case reports, and reviews.

Literature Review

Some clinical guidelines have already added olanzapine as a recommended option for patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy (HEC).5 The NCCN has recommended olanzapine as a first-line option for CINV prophylaxis for patients receiving HEC when added to recommended combination antiemetic regimens, including a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone with or without an NK-1 receptor antagonist.5 The 2016 Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Antiemetics Guidelines Committee discussed the published data about olanzapine, which suggest that it is an effective antiemetic agent, and recommended that olanzapine be considered with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist plus dexamethasone, particularly when nausea is a problem.7

The MASCC/ESMO guidelines mention that patient sedation may be a concern for the 10-mg dose (MASCC level of confidence, low; MASCC level of consensus, low; ESMO level of evidence, II; ESMO grade of recommendation, B).7 Furthermore, the MASCC/ESMO guidelines suggested using olanzapine for breakthrough nausea and vomiting using a 10-mg oral dose of olanzapine daily for 3 days (MASCC level of confidence, moderate; MASCC level of consensus, moderate; ESMO level of evidence, II; ESMO grade of recommendation, B).7

A case series published in 2016 showed that olanzapine 5 mg given orally at night as a single dose provided adequate and ongoing relief of nausea and vomiting, with an acceptable adverse events profile in 13 of 14 evaluable patients.8 The investigators concluded that in comparison with metoclopramide or haloperidol, olanzapine should be considered for first-line therapy for nausea and vomiting in this patient population, but the dose range and the safety profile need to be established by additional clinical studies.8

The role of olanzapine in refractory conditions not related to CINV is limited to case reports or case series, retrospective studies, 1 pilot study, and 1 randomized controlled clinical trial in patients with major depressive disorder.9

Phase 2 Clinical Trials

A phase 2 clinical trial evaluated the effectiveness of olanzapine therapy in combination with palonosetron and dexamethasone for acute and delayed CINV in patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC) and HEC.10 Patients were given olanzapine 10 mg orally on day 1 before chemotherapy and on days 2 to 4 after chemotherapy administration. Dexamethasone (8 mg orally or intravenously for MEC or 20 mg orally or intravenously for HEC) and IV palonosetron 0.25 mg, 30 to 60 minutes, were administered before chemotherapy. Patients received no other antiemetic agent on days 2 to 4.10 The findings showed a significant improvement in controlling CINV with the addition of olanzapine. The investigators concluded that olanzapine, combined with a single dose of dexamethasone and a single dose of palonosetron, was very effective in controlling acute or delayed CINV in patients receiving HEC or MEC regimens. The quality of the evidence demonstrated in this study is limited, because the study was not a randomized controlled trial and had a small sample size of 40 patients.10

Phase 3 Clinical Trials

In 2011, Navari and colleagues conducted a randomized, phase 3 clinical trial to compare the effectiveness of olanzapine, with aprepitant, for the prevention of CINV in patients receiving HEC.11 Patients were randomly assigned to olanzapine, palonosetron, and dexamethasone (OPD; N = 121) or to aprepitant, palonosetron, and dexamethasone (APD; N = 120). The OPD regimen was administered on the day of chemotherapy (day 1) and consisted of IV dexamethasone 20 mg and IV palonosetron 0.25 mg 30 to 60 minutes before chemotherapy administration. All patients also received oral olanzapine 10 mg on day 1, then 10 mg daily on days 2 to 4 after chemotherapy administration. No other antiemetic agents were given on days 2 to 4.11

By contrast, the APD regimen, consisting of IV dexamethasone 12 mg, IV palonosetron 0.25 mg, and oral aprepitant 125 mg, was given 30 to 60 minutes before chemotherapy on day 1. Thereafter, patients received oral aprepitant 80 mg daily on days 2 and 3, and oral dexamethasone 4 mg twice daily on days 2 to 4 postchemotherapy.11

The OPD regimen was more effective than the APD regimen in controlling nausea in the delayed and overall periods. Moreover, olanzapine, combined with a single dose of dexamethasone and a single dose of palonosetron, was very effective at controlling acute and delayed CINV in patients receiving HEC. In terms of safety, olanzapine use was not associated with significant adverse events, which usually include sedation, weight gain, and induction of significant hyperglycemia.11 From a financial point of view, the 4-day cost of treatment with olanzapine is approximately 10% to 20% of the cost of the 3-day regimen of aprepitant treatment.

The results of this study are encouraging for the use of olanzapine as a treatment option for CINV; however, this study was inadequately powered to demonstrate that olanzapine is safe and effective compared with the standard of care.11

The majority of patients in this study had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score of 0 and were predominantly female.11 In addition, the lack of blinding in the clinical trial may reduce the ability to rule out confounding factors or bias.11 Comorbidities, along with patient compliance, can contribute to the effectiveness of the medication and can influence the results.

A double-blind, randomized phase 3 clinical trial compared olanzapine and metoclopramide in the treatment of breakthrough CINV in chemotherapy-naïve patients who received HEC (ie, cisplatin ≥70 mg/m2 or doxorubicin ≥50 mg/m2 and cyclophosphamide ≥600 mg/m2).12 Having no emetic episodes in the 72-hour observation period after the initiation of treatment with olanzapine or with metoclopramide was the primary study outcome. Having no nausea in the 72-hour observation period was the secondary outcome. All patients received IV dexamethasone 12 mg, IV palonosetron 0.25 mg, and IV fosaprepitant 150 mg 30 to 60 minutes before chemotherapy administration. Patients were then randomized to oral metoclopramide 10 mg every 8 hours or to oral olanzapine 10 mg every 24 hours (both for a total of 72 hours).12

Of the 276 enrolled patients, 112 had breakthrough CINV, and 108 were evaluable. During the 72-hour observation period, 70% of patients who received olanzapine had no emesis versus 31% of those who received metoclopramide (P <.01). Of the patients without nausea during the 72-hour observation period, 68% received olanzapine and 23% received metoclopramide

(P <.01). No grade 3 or 4 toxicities (ie, sedation, weight gain, hyperglycemia) occurred in this study. The investigators concluded that olanzapine was significantly more effective in the treatment of breakthrough nausea and vomiting than metoclopramide, and without serious toxicities.12

This study was the first to demonstrate the superiority of olanzapine over metoclopramide in the treatment of breakthrough CINV. Although it was a double-blind, randomized phase 3 clinical trial, the cohort with breakthrough CINV had a small patient population (ie, 112 patients who were randomized to the 2 groups). In addition, the study compared olanzapine with CINV.12

In a large phase 3 randomized, double-blind clinical trial, Navari and colleagues reported a significant effect on controlling CINV by adding olanzapine to the standard antiemetic regimen, with “no nausea” being the primary end point.13 All patients received a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist (ie, IV palonosetron 0.25 mg, granisetron 1 mg intravenously or 2 mg orally, or ondansetron 8 mg orally or intravenously) on chemotherapy day 1; dexamethasone orally (12 mg on day 1, and 8 mg on days 2 to 4); and an NK1-receptor antagonist on day 1 (ie, IV fosaprepitant 150 mg on day 1 or oral aprepitant 125 mg on day 1 and 80 mg on days 2 to 3). In addition, all patients received oral olanzapine 10 mg or a matching placebo on days 1 to 4.13

Absence of chemotherapy-induced nausea was significantly more common with olanzapine than with placebo in the first 24 hours after chemotherapy (74% vs 45%, respectively; P = .002), during the period from 25 to 120 hours after chemotherapy (42% vs 25%, respectively; P = .002), and during the overall 120-hour period (37% vs 22%, respectively; P = .002). In addition, the complete response rate was higher with olanzapine than with placebo during the 3 periods—86% versus 65%, respectively (P <.001); 67% versus 52%, respectively (P = .007); and 64% versus 41%, respectively (P <.001).13

This is the first large randomized, double-blind clinical trial to investigate nausea as the primary end point and vomiting as a secondary end point.13 The study was well-designed, with a balanced distribution of the patient population between the 2 study arms in terms of sex, age, regimen, and diagnosis. However, only 2 HEC regimens were included in this study, so more evidence is needed to verify if adding olanzapine will also be as effective for other HEC regimens. Furthermore, the investigators did not report minimal nausea (ie, score 1-3) as an end point; therefore, partial response to olanzapine compared with placebo was not measured. Despite the tolerability of olanzapine in this study, increased sedation was reported in patients who received olanzapine (compared with placebo) in addition to grade 3 fatigue and hyperglycemia.13

Olanzapine and Quality of Life

Mizukami and colleagues’ double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluated if olanzapine can reduce the frequency of CINV as well as the effect of olanzapine on the patient’s quality of life during chemotherapy.14 The study included hospitalized patients with an ECOG score of 0 to 2 who were scheduled to receive MEC or HEC. The primary outcome measure was total control time from 0 to 120 hours; that is, no vomiting, no acute use of rescue medications, and maximum nausea of 5 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale.14

Patients were randomized to oral olanzapine 5 mg or to oral placebo on day 0 (ie, the day before chemotherapy) and repeated daily through day 5. All patients received IV dexamethasone 9.9 mg on day 1 (ie, day of chemotherapy administration) and IV 6.6 mg daily on days 2 to 4. All patients received a 5-HT3 antagonist (ie, granisetron 3-6 mg on days 1 to 3, ondansetron 4 mg on days 1 to 2, ramosetron 0.6 mg on days 1 to 3, or palonosetron 0.75 mg on day 1) and oral aprepitant 125 mg on day 1 and 80 mg on days 2 to 3. Patients were given IV metoclopramide 10 mg (up to 3 doses daily) as a rescue drug, if needed.14

The patients who were randomized to olanzapine had more favorable outcomes in the 2 study measures. The rate of total control of nausea and vomiting was 59% versus 23% (P = .031); in the delayed phase (ie, 24-120 hours), it was 64% versus 23% (P = .014), respectively, for patients receiving olanzapine versus placebo. The addition of olanzapine to standard antiemetic therapy reduced CINV and improved quality of life in patients receiving HEC or MEC, especially in the delayed phase.14 Appetite-stimulating olanzapine may improve appetite and mood during chemotherapy.

This was the first study to demonstrate that the addition of olanzapine to the usual 3-drug regimen markedly reduced the incidence of CINV. The study also showed that olanzapine had significant secondary benefits in terms of quality of life (ie, appetite, emotion, daily activity scores). Although the study population was small (ie, 44 patients), the study was well-designed, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled.14 Using palonosetron, which has a long half-life, may have an effect on the control of CINV in the delayed phase. In addition, the average age in the olanzapine group was high, which may mean lower risk for CINV in this group.14

A randomized controlled clinical trial investigated the impact of olanzapine on the patient’s quality of life using a CINV questionnaire.15 A total of 229 patients with cancer who received chemotherapy from January 2008 to August 2008 were enrolled and were randomized to olanzapine or to a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. The results showed a significant improvement in patients’ quality of life, global health status, emotional functioning, social functioning, and reduction in fatigue, nausea or vomiting, insomnia, and appetite loss in the olanzapine arm.15

Additional Studies

In 2016, Mukhopadhyay and colleagues conducted a randomized, controlled, assessor-blinded study with 100 chemotherapy-naïve patients to evaluate the role of olanzapine in CINV in patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy (ie, cisplatin, carboplatin, or oxaliplatin).16 The control group (N = 50) received palonosetron and dexamethasone in the approved therapeutic doses from day 1. The study group (N = 50) received olanzapine 10 mg daily on days 1 to 5 in addition to palonosetron and dexamethasone.16

Significantly fewer nausea and vomiting events were reported among the olanzapine arm. The control of delayed emesis was also significantly better in this group, with a complete response rate of 96% versus 42% in the control group (P <.0001). In terms of safety, sedation was more frequently reported in patients who received olanzapine treatment, but no dose-limiting adverse events were reported. Quality of life was also better among the patients who received olanzapine treatment. The investigators concluded that olanzapine was effective as an add-on therapy for the control of CINV.16

Another clinical trial evaluated patients who had CINV refractory to guideline-recommended prophylaxis and breakthrough antiemetics (ie, dopamine antagonists and benzodiazepines) and who received at least 1 dose of olanzapine 5 mg to 10 mg orally.17 The addition of olanzapine to a dopamine antagonist and benzodiazepine demonstrated high efficacy rates for refractory CINV, regardless of chemotherapy emetogenicity.17

Although this was not a randomized controlled clinical trial, and the patient population size (N = 33) was small, these results suggest that the addition of olanzapine to conventional therapies may be of benefit to patients with refractory CINV, regardless of emetogenic potential, sex, age, or antiemetic prophylaxis.17

Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Wang and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis to assess the efficacy of olanzapine for the prevention of CINV associated with MEC or HEC administration.18 The study included 726 patients, of whom 441 were Chinese. The investigators concluded that for the general populations and for Chinese populations, antiemetic regimens that included olanzapine (ie, dosage range, 5-10 mg orally every 24 hours, starting the day of chemotherapy and up to 8 days posttherapy) were more effective at reducing CINV than regimens that did not include olanzapine, especially in the delayed phase of CINV.18

The study limitations that could affect the validity of the results include generalizing the results of multiple trials, a disproportionate number of Chinese patients, and that many of the studies did not follow the standard of care in the terms of medications recommended by evidence-based guidelines.18

A systematic review of 488 patients from 3 clinical trials of CINV prophylaxis and 323 patients from 3 clinical trials of breakthrough CINV showed that olanzapine-containing regimens (ie, 10 mg orally every 24 hours on days 1 through 5) were associated with significant improvements in preventing CINV with the use of HEC or MEC.19 In addition, oral olanzapine, given as 5 mg twice daily or 10 mg once daily every 24 hours, was superior to standard therapy when used as a single agent for breakthrough nausea.19

Another systematic review evaluated the efficacy and safety of olanzapine for CINV prophylaxis as reported in phase 1 and 2 clinical trials.20 The dose of oral olanzapine ranged from as low as 2.5 mg once daily to 15 mg every 24 hours up to 7 days posttherapy. This review included 7 studies with a total of 201 patients. The complete response rates across 4 studies were 97.2%, 83.1%, and 82.8% for the acute, delayed, and overall phases, respectively. The complete control rates for acute, delayed, and overall phases were 92.5%, 87.5%, and 82.5%, respectively.20

The overall no nausea rates were 92.7%, 71.8%, and 70.6% for the acute, delayed, and overall phases, respectively. The overall no emesis rates for the acute, delayed, and overall phases were 100%, 94.5%, and 90.4%, respectively. Fatigue, drowsiness, and disturbed sleep were common side effects. The investigators concluded that olanzapine is safe and effective when used as a prophylaxis for CINV.20

Olanzapine Safety and Patient Adherence

Olanzapine has the potential to lower the threshold for seizure.21 Caution should be advised when prescribing olanzapine in patients with predisposing conditions to seizures.

In one study, olanzapine resulted in a 52% drowsiness rate.22 In a study conducted in a Chinese population, sleepiness during chemotherapy was reported in 73% of patients who received the olanzapine regimen.23 However, the 5% incidence of severe sedation in this study cannot be ignored,23 because this may be potentiated further by other factors, such as comorbidities, advanced age, and concurrent opioid therapy.

Despite being reported as a safe and well-tolerated agent by most patients, some concerns may exist about olanzapine’s safety as an atypical antipsychotic. In a systematic review, Chow and colleagues reported fatigue, drowsiness, and disturbed sleep as common side effects of olanzapine when used for CINV prophylaxis.20

In 2015, Sengupta and colleagues presented a case report of a 30-year-old male patient who had suspected olanzapine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome 5 days after initiation of olanzapine 10 mg daily.24 Although Stevens-Johnson syndrome is a rare adverse reaction, it is a reason for vigilance in prescribing, monitoring for side effects, and caution when using olanzapine in patients with a history of severe drug-induced skin reactions. Long-term side effects of olanzapine include weight gain and onset of diabetes mellitus, but these effects have not been reported with short-term (ie, <1 week) use.6

Moreover, olanzapine may have significant drug–drug interactions that require dose or frequency adjustment, additional monitoring, and/or selection of alternative therapy. As an example, the concomitant use of olanzapine and metoclopramide is not recommended, because this combination may increase the risk for extrapyramidal symptoms.25 Olanzapine may also increase the risk for QT interval prolongation when combined with other QT-prolonging agents.25

Patient-specific factors and comorbidities, in addition to olanzapine drug–drug interactions, need to be taken into consideration before prescribing olanzapine. Before starting olanzapine therapy, the drug’s benefits should be weighed against any potential risks.

The reported sedation caused by olanzapine therapy should be taken into consideration,16 because it can be a troublesome side effect in patients who are receiving other sedating or central nervous system–depressing agents.

The Role of the Pharmacist

Pharmacists can play a significant role in the management of supportive care issues, such as CINV management and prevention and patient counseling and education. To improve patient adherence to treatment, it is crucial for the pharmacist to counsel patients on the importance of taking their antiemetic drugs at home.

Pharmacists who are knowledgeable about chemotherapy are in a unique position to improve the quality of care for patients, through collaboration with oncology physicians, nurses, and other cancer care specialists. Discussion of the advantages and limitations of treatment options, proper dosing, and avoidance of drug interactions can improve outcomes and minimize undesirable effects. In addition, pharmacists are actively involved in research programs and participate in guideline development.26

Another study concluded that a pharmacist-run protocol for CINV management was as effective as the standard of care.27 Protocols that are based on practice guidelines may offer the advantage of care standardization and potential cost-savings, according to that study.27

Conclusions

Overall, the findings of these clinical trials are encouraging and support the use of olanzapine as a treatment option in acute, delayed, and refractory CINV. According to these studies, olanzapine is an effective therapeutic option to manage CINV in patients receiving MEC or HEC, with minor reported side effects when used for short courses.

The available evidence supports the use of an olanzapine-containing regimen as a primary treatment option for CINV prevention. As for all medications, this recommendation needs to be considered in light of certain comorbid conditions, the risk for side effects and potential drug–drug interactions.

The place of olanzapine in the treatment of CINV in patients receiving MEC or HEC, the optimal dosing and duration of therapy of olanzapine for adults and pediatrics, and the integration of olanzapine in different chemotherapy treatment plans will likely become more defined as research continues. Cost-effectiveness analysis of olanzapine use compared with conventional regimens is also needed to assess its cost-effectiveness versus available options.

Additional studies are needed to establish the ideal regimen for various patient subgroups (ie, personalized therapy), the optimal olanzapine dose, and the cost-effectiveness of olanzapine-containing regimens.

Author Disclosure Statement

Mr Al-Quteimat, Mr Tollison, and Dr Siddiqui have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Rao KV, Faso A. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: optimizing prevention and management. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2012;5:232-240.

- Roila F, Hesketh PJ, Herrstedt J; for the Antiemetic Subcommitte of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. Prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced emesis: results of the 2004 Perugia International Antiemetic Consensus Conference. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:20-28.

- Janelsins MC, Tejani M, Kamen C, et al. Current pharmacotherapy for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in cancer patients. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:757-766.

- Warr D. Prognostic factors for chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;722:192-196.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®): Antiemesis. Version 3.2018. June 11, 2018. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/antiemesis.pdf. Accessed February 22, 2019. To view the most complete version of the guideline, go online to NCCN.org. NCCN makes no warranties of any kind whatsoever regarding their content, use or application and disclaims any responsibility for their application or use in any way.

- Navari RM. Olanzapine for the prevention and treatment of chronic nausea and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;722:180-186.

- Roila F, Molassiotis A, Herrstedt J, et al. 2016 MASCC and ESMO guideline update for the prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 5):v119-v133.

- MacKintosh D. Olanzapine in the management of difficult to control nausea and vomiting in a palliative care population: a case series. J Palliat Med. 2016;19:87-90.

- Langley-DeGroot M, Ma JD, Hirst J, Roeland EJ. Olanzapine in the treatment of refractory nausea and vomiting: a case report and review of the literature. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2015;29:148-152.

- Navari RM, Einhorn LH, Loehrer PJ Sr, et al. A phase II trial of olanzapine, dexamethasone, and palonosetron for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a Hoosier oncology group study. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:1285-1291.

- Navari RM, Gray SE, Kerr AC. Olanzapine versus aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a randomized phase III trial. J Support Oncol. 2011;9:188-195.

- Navari RM, Nagy CK, Gray SE. The use of olanzapine versus metoclopramide for the treatment of breakthrough chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1655-1663.

- Navari RM, Qin R, Ruddy KJ, et al. Olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:134-142.

- Mizukami N, Yamauchi M, Koike K, et al. Olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47:542-550.

- Liu J, Tan L, Zhang H, et al. QoL evaluation of olanzapine for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting comparing with 5-HT3 receptor antagonist. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2015;24:436-443.

- Mukhopadhyay S, Kwatra G, Alice KP, Badyal D. Role of olanzapine in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting on platinum-based chemotherapy patients: a randomized controlled study. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:145-154. Erratum in: Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:155-156.

- Vig S, Seibert L, Green MR. Olanzapine is effective for refractory chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting irrespective of chemotherapy emetogenicity. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:77-82.

- Wang XF, Feng Y, Chen Y, et al. A meta-analysis of olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4813.

- Hocking CM, Kichenadasse G. Olanzapine for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:1143-1151.

- Chow R, Chiu L, Navari R, et al. Efficacy and safety of olanzapine for the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) as reported in phase I and II studies: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:1001-1008.

- Behere RV, Anjith D, Rao NP, et al. Olanzapine-induced clinical seizure: a case report. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32:297-298.

- Abe M, Kasamatsu Y, Kado N, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine combined therapy for patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy resistant to standard antiemetic therapy. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:956785.

- Tan L, Liu J, Liu X, et al. Clinical research of olanzapine for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:131.

- Sengupta S, Chetia DJ, Nath S, Timungpi B. Olanzapine induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Delhi Psychiatry Journal. 2015;18:206-207.

- Umar RM. Drug-drug interactions between antiemetics used in cancer patients. J Oncological Sciences. 2018;4:142-146

- Jupp J, Pasetka M, Soefje S, Schwartz RN. Pharmacists: integral to the management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:3352-3353.

- Elshaboury R, Green K. Pharmacist-driven management of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting in hospitalized adult oncology patients. A retrospective comparative study. Innovations in Pharmacy. 2011;2:Article 52.