The previous installment in this cancer care series examined the growing importance of oral therapies for the treatment of cancer and the implications of patient adherence on its success. At the present time, more than 20 oral medications are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for first-line treatment of cancer. A number of other oral agents are used for tumors that have relapsed or are refractory to initial treatment, and about 25% of the oncology research pipeline consists of oral compounds.1 This is in addition to self-administered subcutaneous therapies for the home environment that are under FDA review. When cancer medications are administered orally in the home environment rather than in the clinic or hospital, the rates of adherence range from 15% to 97%.2 For example, at the end of the first year of treatment with adjuvant hormonal treatment (AHT) for early-stage breast cancer, only 79% of patients remained on therapy without a gap exceeding 60 days and 85% without a gap exceeding 180 days. By year 5, only 27% and 29% remained without 60- and 180-day gaps, respectively.3

In another study of AHT, patients with a medication possession ratio (MPR) >80% had a statistically significantly higher 10-year survival rate than those with a lesser MPR (82% vs 78%).4 (MPR is a metric derived from electronic prescription records based on refill patterns over time, and 80% is an arbitrary cut point for adherence used by many investigators.) The same study found survival at 10 years to be 81% for those who continued therapy versus 74% for those who had discontinued it. Nonadherence has also been shown to produce substantial detriment in clinical outcomes in chronic myeloid leukemia and childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia.5-8 For each of these disorders, prolonged oral therapy has been the standard of care for a decade or more. It is likely that negative consequences of nonadherence with other oral cancer medications will be documented in the future as their role in therapy matures. The purpose of this article is to discuss the results of available research on maximizing adherence and suggest best practices to improve clinical outcomes.

Identifying Patients at Risk for Nonadherence

Direct communication with all patients about their personal barriers to taking daily therapy for a prolonged period is an important aspect to maximizing adherence, although time constraints in a busy practice may make this difficult. As described in detail in the previous article in this series, a number of barriers and risk factors have been associated with poor adherence and can be considered when developing a triage strategy for those most in need of in-depth discussion9-17:

- Adverse events

- Forgetfulness

- Missed appointments

- Competing priorities (medical and/or social)

- Lack of information

- Higher out-of-pocket costs

- Longer duration of treatment

- Poor relationship with healthcare provider

- Higher levels of comorbidity

- Regimens with high dosing frequency

- History of low out-of-pocket pharmacy costs in the year prior to cancer diagnosis

- Belief that patient has little influence over his or her own health

- Belief that no benefit is to be gained from medication

- Families in conflict

- Age (conflicting data)

Maximizing Adherence Begins With the Therapeutic Relationship

By far, the most prevalent modifiable aspect of adherence discussed in the literature is that of the relationship between the healthcare provider and patient. Integral to this relationship are communication skills. Several studies have suggested that when a patient’s expectations of a warm interaction with a physician who appears to be technically competent and gives adequate information are not met, the patient is less satisfied and less likely to comply with his or her medical regimen.18 For example, when a Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale (MISS) was used to measure patients’ perception of physician behavior, their affective satisfaction was associated most with “exposition exchanges” at the beginning of interviews during which a patient tells his or her own story while the physician listens attentively and acknowledges what is said. During this exchange, much information about the patient’s beliefs, attitudes, cultural context, psychosocial implications, and emotional challenges can be learned. These assessments have been discussed as the Health Belief Model for over 30 years.19

In the MISS study, the patients’ cognitive satisfaction was found to be significantly correlated with the incidence of “feedback exchanges” at the end of interviews when the patients are given a chance to acknowledge receipt of information and ask questions. At this time, a patient’s adherence intention, including required lifestyle alterations and the ensuing psychosocial implications, can be explored and negotiated. Acknowledgment of any differences in opinion at this time is an important part of building a respectful relationship.20 A study of psychological distress before and 3 months after treatment for early-stage breast cancer showed that patient-reported communication problems have long-lasting effects, resulting in confusion, anxiety, depression, anger, and difficulty asking questions and understanding information.21

Authors of a recent meta-analysis based on a search of the literature published from 1949 through August 2008 examined 106 correlational studies on physician communication and found that patients of physicians who communicate well have a 19% higher adherence to treatment.22 In addition, the same researchers analyzed 21 experimental interventions and determined that training in communication skills results in an overall statistically significant improvement in patient adherence of about 12%. The authors concluded that such training should be broad-based and concentrate on verbal and nonverbal skills, affective/psychosocial behavior, and the creation of opportunities for active patient involvement. A consensus developed by a group of European experts on cancer communication skills training (CST) recommended that23:

- CST be required at all levels of professional education

- A course of at least 3 days be conducted to transfer skills into clinical practice

- Courses be learner centered and conducted in small groups (4-6 persons) with a trained facilitator to promote active participation and interactivity

- Trainers should be healthcare professionals with credibility and experience in an oncology setting

- CST programs should have financial support (unrestricted grants) from a variety of sources, be supported by professional societies, and be awarded continuing education credits

Specific Strategies to Improve Adherence

Although numerous risk factors have been identified as contributing to nonadherence, surprisingly little research has been conducted to identify and support specific improvement techniques. Information on medications shown to have more favorable adherence profiles would be valuable. For example, a recent claims database analysis of adherence to agents for second-line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia was published and demonstrated that patients who were prescribed nilotinib had a higher risk of nonadherence (MPR <85%) than those on dasatinib (hazard ratio 1.6, 95% confidence interval 1.0-2.4).24 Additional research of this type is needed.

Results of multivariate analysis suggested no direct effect of depression on medication adherence; rather, evidence indicated that the relationship between depression and adherence was mediated by “planned behavior processes” by which patients’ depression leads to less favorable attitudes toward treatment plans and toward perceptions that they have little control over engaging in their treatment behaviors.25 Indirectly, evaluation and treatment for depression may engender more positive attitudes, and therefore the effects of more favorable intentions should be explored.

Based on the observation that forgetfulness and complicated regimens are associated with nonadherence, a small pilot study of 25 patients receiving capecitabine for 14 days of a 21-day cycle evaluated traditional packaging versus a daily pillbox (one cycle of each method in a crossover fashion).26 Patients preferred the daily pillbox method and thought it was helpful. No difference in adherence was noted, but the short-term design limited adequate evaluation of the method.

Many of the factors described above have been associated with nonadherence in teenage and young adult patients with cancer. An extensive review published in 2011 described only 1 study addressing an intervention, a video-game activity focusing on behavioral issues related to cancer treatment.27 This randomized trial was conducted at 34 centers in the United States, Canada, and Australia.28 Enrolled in the study were 375 patients between the ages of 13 and 29 years who had received a recent diagnosis either of cancer or of relapse and who expected to continue treatment for at least 4 months. A video-game intervention was designed based on earlier research suggesting the modality to be linked to indicators of effective disease management, including blood glucose levels, self-care behaviors, and emergency department use. All patients received a minicomputer game unit, with either a commercial game alone or a commercial game plus the cancer intervention game.

The intervention game, called “Re-mission,” involved a nanobot in a 3-dimensional environment within the bodies of young patients with cancer. Play included destroying cancer cells and managing adverse effects using chemotherapy, antibiotics, and antiemetics as ammunition. Neither the nanobot nor the virtual patient “died” during the game. Patients were asked to play the game(s) for at least 1 hour per week during the 3-month study period, and serial outcome assessments were collected at 1 and 3 months after baseline. Attrition rates were high during the study (17% in the intervention group and 21% in the control group). Adherence to mercaptopurine and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, in the patients prescribed those therapies, was greater in the intervention group. Monitoring of mercaptopurine metabolite levels showed significantly higher levels over time in the intervention group compared with the control group. Similarly, readings obtained with an electronic pill vial cap indicated 16% greater adherence with the antibiotic. Knowledge and perception of self-efficacy were also increased, but self-reports of adherence, stress, and quality of life were not.

Had it reached completion, a large and simply designed trial in Germany would have provided useful information on a practical approach to maximize adherence. It sought to enroll almost 5000 adult patients to determine if the addition of written information via mail combined with a reminder service would improve adherence and persistence with adjuvant anastrozole therapy for early-stage breast cancer. More than 3000 patients had been accrued into the trial by the beginning of 2009, but the dropout rate was high, and the study was terminated after the investigators determined that insufficient data would be available at the 24-month follow-up point to conduct an analysis.29,30 Unfortunately, it is unknown whether these difficulties were a reflection primarily of the requirements of the research design or of the adherence method itself.

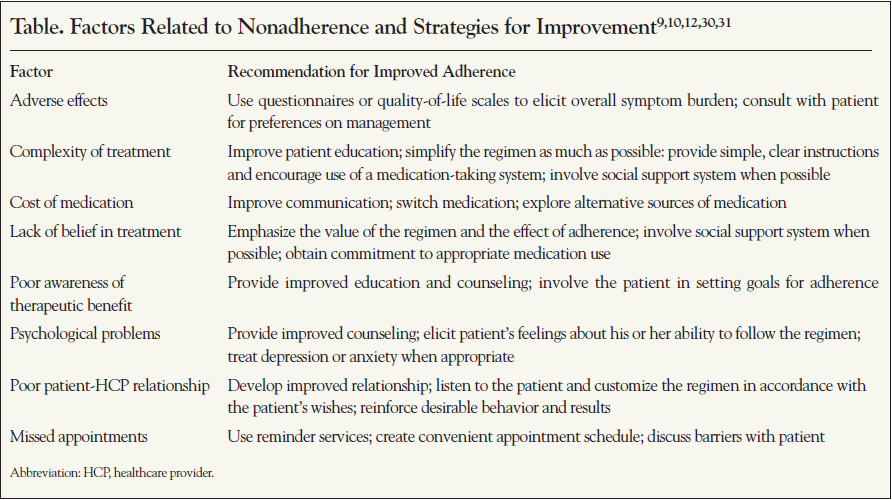

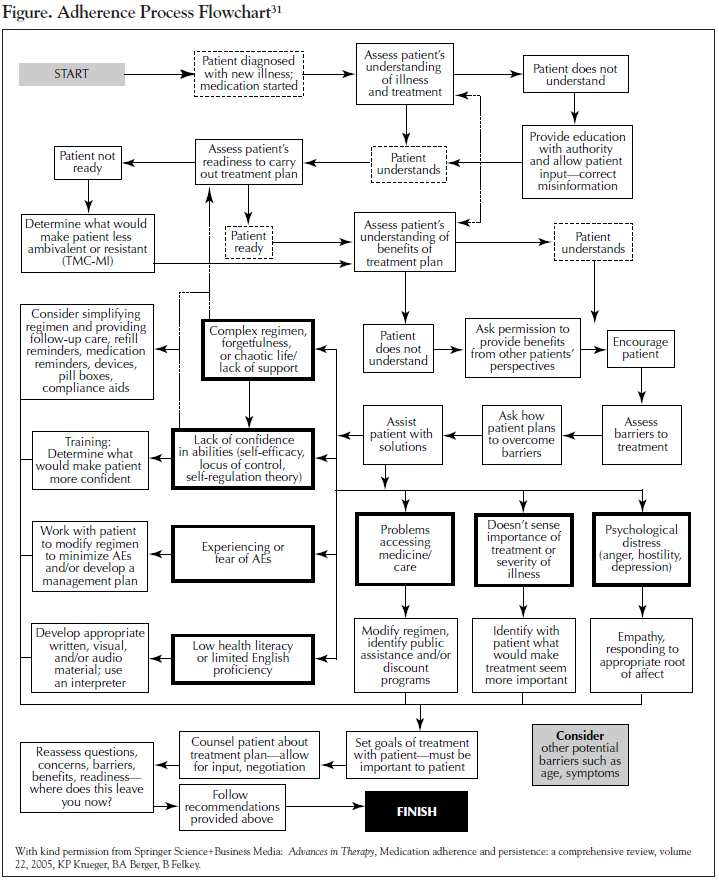

Due to the lack of evidence-based guidance on interventions to improve therapy adherence, recommendations from experts in the field are important to consider. A number of reviews have been published. Recommended methods to address specific risk factors for nonadherence are shown in the Table and in the flowchart in the Figure. In addition to being employed during initial therapy discussions with the patient, the approaches described should also be a part of routine follow-up to reinforce earlier exchanges and detect any new issues that have arisen. Once a patient is prescribed a regimen, the estimation of whether that patient is adherent is not easy.20 Physicians’ reliance on their own intuition is often ineffective; physicians are typically not highly accurate in assessing whether a patient is adhering to therapy and why a patient chooses to adhere. Asking patients nonjudgmentally about medication-taking behavior is a practical strategy to identify poor adherence, while attempts to “catch” patients in nonadherence can be problematic because patients are less likely to be truthful if they feel a risk of criticism. Thus, many of the interpersonal factors that are associated with the clinician-patient relationship come into play with difficulties in adherence assessment. The risk of worsening adherence behavior itself, thus potentially resulting in worsening overall outcomes, should be considered during every patient encounter.

Summary

Poor adherence to oral or self-administered subcutaneous cancer medications is common, contributing to significant worsening of disease. More controlled research is needed to document specific techniques that are effective in improving adherence. Until such evidence-based guidance is available, healthcare professionals should work to enhance adherence by emphasizing the value of the patient’s regimen and customizing the regimen to the patient’s lifestyle as much as possible. Continuing education in communication skills relating to adherence is recommended. Although new technologies are attractive methods to augment adherence to therapy, the relationship with the patient and substantive discussions about the impact of therapy remain the most important contributors to success.

References

- Schwartz RN, Eng KJ, Frieze DA, et al. NCCN Task Force report: specialty pharmacy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8(suppl 4):S1-S12.

- Hohneker J, Shah-Mehta S, Brandt PS. Perspectives on adherence and persistence with oral medications for cancer treatment. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:65-67.

- Nekhlyudov L, Li L, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Five-year patterns of adjuvant hormonal therapy use, persistence, and adherence among insured women with earlystage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:681-689.

- Hershman DL, Shao T, Kushi LH, et al. Early discontinuation and non-adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy are associated with increased mortality in women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:529-537.

- Lennard L, Lilleyman JS. Variable mercaptopurine metabolism and treatment outcome in childhood lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1816-1823.

- Lilleyman JS, Lennard L. Mercaptopurine metabolism and risk of relapse in childhood lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 1994;343:1188-1190.

- Noens L, van Lierde MA, De Bock R, et al. Prevalence, determinants, and outcomes of nonadherence to imatinib therapy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: the ADAGIO study. Blood. 2009;113:5401-5411.

- Ibrahim AR, Eliasson L, Apperley JF, et al. Poor adherence is the main reason for loss of CCyR and imatinib failure for chronic myeloid leukemia patients on long-term therapy. Blood. 2011;117:3733-3736.

- Oberguggenberger A, Hubalek M, Sztankay M, et al. Is the toxicity of adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy underestimated? Complementary information from patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128:553-561.

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:487-497.

- Sedjo RL, Devine S. Predictors of non-adherence to aromatase inhibitors among commercially insured women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125:191-200.

- Grunfeld EA, Hunter MS, Sikka P, et al. Aherence beliefs among breast cancer patients taking tamoxifen. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:97-102.

- Claxton AJ, Cramer J, Pierce C. A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1296-1310.

- DiMatteo MR, Haskard KB, Williams S. Health beliefs, disease severity, and patient adherence: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2007;45:521-528.

- Atkins L, Fallowfield L. Intentional and non-intentional non-adherence to medication amongst breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:2271-2276.

- DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23:207-218.

- Landier W. Age span challenges: adherence in pediatric oncology. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2011;27:142-153.

- Wolf MH, Putnam SM, James SA, Stiles WB. The Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale: development of a scale to measure patient perceptions of physician behavior. J Behav Med. 1978;1:391-401.

- Moore S. Facilitating oral chemotherapy treatment and compliance through patient/family-focused education. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30:112-122.

- Martin LR, Williams SL, Haskard KB, et al. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2005;1:189-199.

- Lerman C, Daly M, Walsh WP, et al. Communication between patients with breast cancer and health care providers: determinants and implications. Cancer. 1993;72:2612-2620.

- Zolnierek KBH, DiMatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47:826-834.

- Stiefel F, Barth J, Bensing J, et al. Communication skills training in oncology: a position paper based on a consensus meeting among European experts in 2009. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:204-207.

- Yood MU, Oliveria SA, Cziraky M, et al. Adherence to treatment with second-line therapies, dasatinib and nilotinib, in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:213-219.

- Manning M, Bettencourt BA. Depression and medication adherence among breast cancer survivors: bridging the gap with the theory of planned behaviour. Psychol Health. 2011;26:1173-1187.

- Macintosh PW, Pond GR, Pond BJ, et al. A comparison of patient adherence and preference of packaging method for oral anticancer agents using conventional pill bottles versus daily pill boxes. Eur J Cancer Care. 2007;16:380-386.

- Kondryn HJ, Edmondson CL, Hill J, et al. Treatment non-adherence in teenage and young adult patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:100-108.

- Kato PM, Cole SW, Bradlyn AS, et al. A video game improves behavioral outcomes in adolescents and young adults with cancer: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e305-e317.

- Patient’s Anastrozole Compliance to Therapy Programme (PACT). http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00555867. Accessed January 30, 2012.

- Hadji P. Improving compliance and persistence to adjuvant tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitor therapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;73:156-166.

- Krueger KP, Berger BA, Felkey B. Medication adherence and persistence: a comprehensive review. Adv Ther. 2005;22:313-356.