Recent statistics from the National Cancer Institute estimate that 25% of adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are expected to survive for ≥3 years.1 Depending on other prognostic factors, such as duration of first remission, age, performance status, cytogenetics, and prior hematopoietic stem cell transplant, the overall survival of patients with relapsed/refractory disease at 5 years was <5%, and response rates were between 5% and 50%.1,2 Poor prognosis may be related to increasing age, cytogenetics and molecular mutations, and duration of first remission. Specifically, the absence of complete remission after the first induction therapy, and a remission duration of less than 6 months have been linked to worst patient outcomes.2

Although the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines for AML (version 1.2015) offer several options for the treatment of relapsed/refractory patients, no standard or preferred salvage regimen is available for this population.3 Regimens are typically chosen based on the discretion of the institution and the provider. Several suggested regimens contain purine/pyrimidine analogues with or without an anthracycline.3 One regimen in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines for AML includes cladribine, cytarabine, and filgrastim, with mitoxantrone (CLAG-M) or without mitoxantrone (CLAG).3 At this time, the medical literature offers few studies on the efficacy of the CLAG/CLAG-M regimen in patients with AML.

To add to the body of literature describing this regimen in patients with relapsed/refractory AML, we conducted a retrospective analysis examining response rates in patients with AML after completion of CLAG/CLAG-M.

Methods

This study was a retrospective analysis of patients with relapsed/refractory AML who received treatment with CLAG/CLAG-M: cladribine 5 mg/m2 intravenously (IV) days 1 to 5, cytarabine 2 g/m2 IV days 1 to 5, and filgrastim 300 mcg subcutaneously days 1 to 5, with or without mitoxantrone 10 mg/m2 IV days 1 to 3. Cladribine was infused over 2 hours, followed by a 4-hour infusion of cytarabine. Mitoxantrone was prepared in a small volume intravenously and administered during the course of 10 minutes.

Patients could have received the regimen at any point during their salvage therapy, from the time of their first relapse to subsequent salvage therapy. The primary end point of interest was complete response (CR) after completion of the CLAG or CLAG-M regimen. Secondary end points included with CR incomplete recovery (CRi), overall response (CR + CRi), duration of remission, overall survival, adverse effects, and number of patients who transitioned to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

For the purpose of this study, CR was defined as bone marrow blasts <5%, absolute neutrophil count >1.0 × 109/L (1000/µL), and platelet count >100 × 109/L (100,000/µL) after bone marrow recovery. CRi was defined as meeting all CR criteria except for residual neutropenia or thrombocytopenia. Refractory patients were defined as not achieving CR after their first induction therapy. Relapsed patients were defined as having disease recurrence after previously achieving CR.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were ≥18 years of age, diagnosed with relapsed or refractory AML, and treated with CLAG/CLAG-M regimens at New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center (NYP-WC) between January 2010 and December 2012. Patients who did not receive these regimens or who had a diagnosis other than AML were excluded from the review.

Variables collected during the analysis were age, sex, risk status for AML based on baseline cytogenetics, and molecular abnormalities as defined by National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines, round of therapy (eg, first, second, or subsequent salvage therapy), first induction regimen, and duration of first CR. The retrospective analysis was approved by the NYP-WC Institutional Review Board.

Results

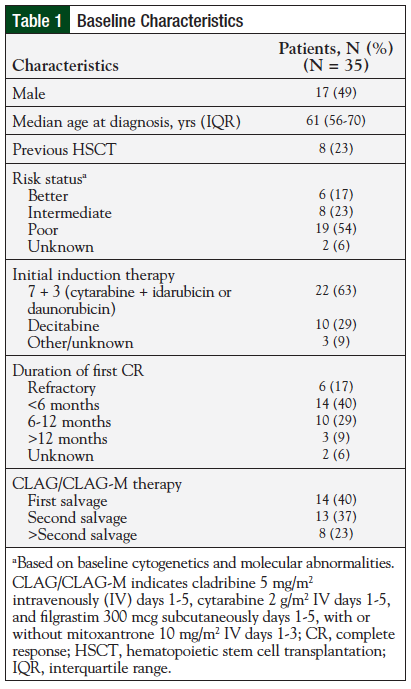

Overall, the review included 35 patients with relapsed/refractory AML. Eight patients previously underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The majority of patients in this study received CLAG or CLAG-M as either first or second salvage therapy. In addition, 8 (23%) patients received therapy subsequently after the second salvage. Table 1 includes the baseline characteristics for the study population.

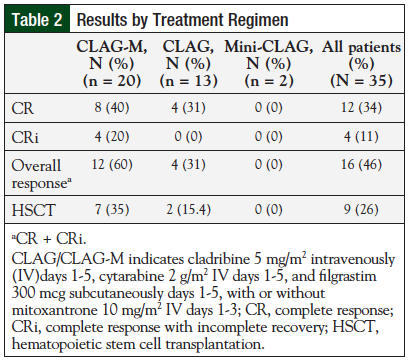

Of the 35 patients included in the review, 20 (57%) received treatment with CLAG-M, 13 (37%) received CLAG, and 2 (6%) received a shortened, 3-day version of CLAG (“mini-CLAG” for the purpose of this study). Table 2 includes results by treatment regimen.

In total, 12 (34%) patients achieved CR, 4 (11%) patients achieved CRi, and 16 (46%) patients achieved CR + CRi. When analyzed by regimen variation, response rates were greater in patients treated with CLAG-M compared with patients treated with CLAG or mini-CLAG. Eight (40%) patients in the CLAG-M group achieved CR and 4 (20%) patients achieved CRi.

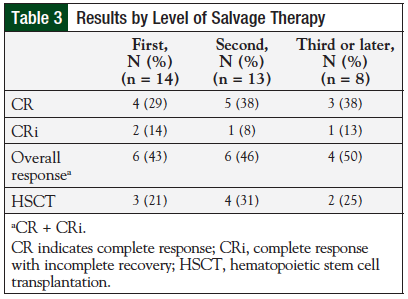

Overall response in the CLAG-M group was 60%, compared with 4 (31%) patients who achieved CR or CRi with CLAG, and 0 patients with CR or CRi in the mini-CLAG cohort. Response rates by level of salvage therapy appear in Table 3.

Overall, 4 (29%) of 14 patients who received CLAG or CLAG-M as a first salvage therapy regimen achieved CR. Five (38%) of 13 patients who received these regimens as second salvage therapy achieved CR. Three (38%) of 8 patients achieved CR during a third or later salvage therapy with CLAG or CLAG-M. Although this information was collected as part of the baseline characteristics, initial cytogenetics, initial white cell count, and first induction therapy regimen did not affect response rates in this review. Of the 8 patients who had previously received hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, 3 (38%) achieved CR or CRi.

After treatment, 9 (56%) of 16 patients achieving a response were able to proceed to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. For the 7 patients not proceeding to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, the median duration of CR was 4 months (range, 1-7 months).

Survival data were available for 34 of 35 patients. Median overall survival was 6 months (range, 0-39 months). One patient who received CLAG-M and proceeded to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation is still alive and in remission 39 months posttreatment.

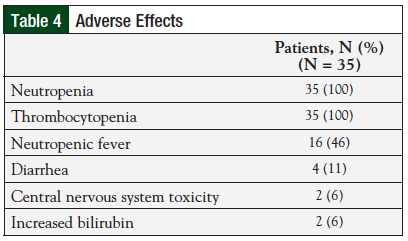

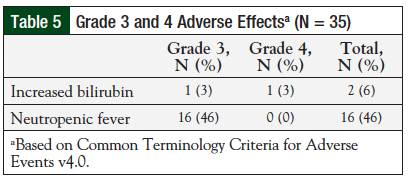

Overall, the regimen was well-tolerated (Table 4). All 35 (100%) patients reported hematologic toxicities, including neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. Four (11%) patients reported diarrhea, of which 3 (9%) cases were a result of the Clostridium difficile infection. Two (6%) patients had side effects affecting the central nervous system, including tremors and encephalopathy. In addition, 2 (6%) patients reported a rash during treatment. Incidence of grade 3 or 4 adverse events was low (Table 5). Two patients died during treatment before receiving the full therapy course; however, these were determined to be unrelated to therapy.

Discussion

This retrospective study examined CR rates in patients with relapsed/refractory AML after CLAG/CLAG-M therapy.

Although there is no standard salvage regimen for relapsed/refractory AML, several agent combinations have been studied. Many of these regimens contain a combination of agents including a purine analogue, such as cladribine, fludarabine phosphate, or clofarabine. CR rates with CLAG or CLAG-M range between 30% and 60%.4-7 Another regimen comprising a purine analogue, a pyrimidine analogue, and a human granulocyte colony stimulating factor, with or without an anthracycline, is FLAG-Ida—fludarabine phosphate, cytarabine, and filgrastim, with or without idarubicin. This regimen has been extensively studied in relapsed/refractory AML. For FLAG and FLAG-Ida, CR rates have ranged between 30% and 80%, with most studies reporting a CR rate of approximately 50%.8-12 A third purine analogue, clofarabine, has also been studied in combination therapy for relapsed AML, with similar CR rates.13

Robak and colleagues conducted a phase 2, prospective, noncomparator trial of CLAG in patients with relapsed/refractory AML.4 This trial included 20 patients, 10 (50%) of whom were able to achieve CR with CLAG therapy.4 A second, retrospective study by Price and colleagues compared CLAG with another common salvage regimen—etoposide, cytarabine, and mitoxantrone hydrochloride (MEC).5 This study showed significantly higher response rates, overall survival, and relapse-free survival with CLAG compared with MEC. The authors reported that 45.5% of patients with primary refractory disease achieved CR with CLAG versus 22.2% with MEC. For patients in first relapse, 36.8% of patients achieved CR with CLAG versus 25.9% with MEC.5

Two studies from the Polish Adult Leukemia Group explored CLAG-M in patients with relapsed/refractory AML.6,7 A phase 2 study by Wrzesień-Kuś and colleagues in 2005 included 43 patients with relapsed or refractory AML who received induction treatment with CLAG-M.6 In this study, 49% of patients treated achieved CR.6 A second study by Wierzbowska and colleagues utilized the same study design and regimens used in the study by Wrzesień-Kuś and colleagues, but included 118 patients.7 Among these patients, 66 (58%) achieved CR after 1 or 2 induction cycles of CLAG-M.7 Another small, retrospective analysis examined 24 patients who received CLAG or CLAG-M.14 The authors reported a CR rate of 53% when the regimen was used as induction chemotherapy, and 44% when used as salvage treatment.14

Results of published studies are similar to those found in our retrospective study. Patients included in prospective trials, however, were allowed a second induction with the same regimen after achieving a partial response to the first cycle.5-7 This second induction may have also increased overall response rates, compared with patients in our retrospective study, where CR rates were only examined after 1 cycle of CLAG/CLAG-M.

Our study has several limitations. In addition to being a single-center, noncomparative retrospective review, the selection of the study regimen lacked standard criteria. Although certain factors, including age, performance status, and comorbid conditions, may have played a role in deciding if a patient should receive mitoxantrone or a shortened treatment course, there were no set, institutional guidelines for this decision. Although this information was collected as part of the baseline characteristics, initial cytogenetics, initial white cell count, and first induction therapy regimen did not appear to affect response rates in this review. A formal, statistical analysis with stratification by risk status, however, was not performed. In addition, the retrospective nature of this review made accurate analysis of adverse effects challenging. The main toxicities of this regimen are hematologic in nature and include neutropenia and thrombocytopenia. In addition to response rates, several patients successfully transitioned to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation after CLAG/CLAG-M therapy. Nine (56%) of 16 patients achieving a response were able to receive hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. The ability to transition to transplantation in this patient population is extremely important because allogeneic bone marrow transplantation generally results in the lowest incidence of relapse when compared with additional chemotherapy.

Conclusion

This review demonstrates similar CR rates to previously published CLAG/CLAG-M studies. CLAG/CLAG-M is an effective salvage regimen for relapsed/refractory AML.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Ippoliti is a Speaker for Sigma Tau and a Consultant for HealthHelp. Dr Thomas and Dr Feldman reported no conflicts of interest. No funding was provided for this study.

References

- National Cancer Institute. Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treatment (PDQ®). www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/adultAML/healthprofessional. Updated January 9, 2015. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- Giles F, O’Brien S, Cortes J, et al. Outcome of patients with acute myelogenous leukemia after second salvage therapy. Cancer. 2005;104:547-554.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Acute myeloid leukemia. NCCN Guidelines. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/aml.pdf. Accessed January 23, 2015.

- Robak T, Wrzesień-Kuś A, Lech-Marańda E, et al. Combination regimen of cladribine (2-chlorodeoxyadenosine), cytarabine and G-CSF (CLAG) as induction therapy for patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2000;39:121-129.

- Price SL, Lancet JE, George TJ, et al. Salvage chemotherapy regimens for acute myeloid leukemia: is one better? Efficacy comparison between CLAG and MEC regimens. Leuk Res. 2011;35:301-304.

- Wrzesień-Kuś A, Robak T, Wierzbowska A, et al. A multicenter, open, noncomparative, phase II study of the combination of cladribine (2-chlorodeoxyadenosine), cytarabine, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and mitoxantrone as induction therapy in refractory acute myeloid leukemia: a report of the Polish Adult Leukemia Group. Ann Hematol. 2005;84:557-564.

- Wierzbowska A, Robak T, Pluta A, et al. Cladribine combined with high doses of arabinoside cytosine, mitoxantrone, and G-CSF (CLAG-M) is a highly effective salvage regimen in patients with refractory and relapsed acute myeloid leukemia of the poor risk: a final report of the Polish Adult Leukemia Group. Eur J Haematol. 2008;80:115-126.

- Steinmetz HT, Schulz A, Staib P, et al. Phase-II trial of idarubicin, fludarabine, cytosine arabinoside, and filgrastim (Ida-FLAG) for treatment of refractory, relapsed, and secondary AML. Ann Hematol. 1999;78:418-425.

- Jackson G, Taylor P, Smith GM, et al. A multicenter, open, non-comparative phase II study of a combination of fludarabine phosphate, cytarabine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia and de novo refractory anaemia with excess of blasts in transformation. Br J Haematol. 2001; 112:127-137.

- de la Rubia J, Regadera AI, Martin G, et al. FLAG-Ida regimen (fludarabine, cytarabine, idarubicin and G-CSF) in the treatment of patients with high risk myeloid malignancies. Leuk Res. 2002;26:725-730.

- Carella MA, Cascavilla M, Greco MM, et al. Treatment of poor risk acute myeloid leukemia with fludarabine, cytarabine and G-CSF (flag regimen): a single centre study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001;40:295-303.

- Huhmann IM, Watzke HH, Geissler K, et al. FLAG (fludarabine, cytosine arabinoside, G-CSF) for refractory and relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol. 1996;73:265-271.

- Scappini B, Gianfaldoni G, Caracciolo F, et al. Cytarabine and clofarabine after high-dose cytarabine in relapsed or refractory AML patients. Am J Hematol. 2012;87: 1047-1051.

- Martin MG, Welch JS, Augustin K, et al. Cladribine in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia: a single-institution experience. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9: 298-301.