Anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are routinely used for the first- and second-line treatment of patients with relapsed or metastatic renal-cell carcinoma (RCC). The targeted TKIs that are often recommended for metastatic RCC include sunitinib, pazopanib, cabozantinib, lenvatinib, everolimus, and axitinib.1-4 Adverse events of any grade can frequently occur in patients with metastatic RCC who are receiving a TKI, which can lead to reducing the drug’s dose, drug therapy interruption, or treatment discontinuation.2-4 In clinical trials of patients with metastatic RCC, approximately 46% of patients receiving these targeted agents as monotherapy required dose reductions.2,5

Because of frequently occurring adverse events, there is an ongoing effort to establish optimal dosing strategies for TKIs to reduce the associated side effects while maintaining the drugs’ efficacy.6 Several studies that support reduced starting doses of TKIs have been conducted in patients with lung cancer, metastatic colorectal cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma.7-9 However, the data regarding patients with metastatic RCC are limited to studies that have evaluated the impact of dose reductions and/or alternate dosing schedules of TKIs in patients who are unable to tolerate standard dosing as a result of grades 2 to 4 adverse events.2,5,10-12 In addition, the available data are clouded by the limited drug selection and the presentation of conflicting conclusions.2,5,10-14

Despite the limited published evidence, the clinical practice at the Georgia Cancer Center-Laney Walker Campus provides empiric evidence for initial dose reductions of TKIs in patients with metastatic RCC. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of different starting doses of TKIs on various clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic RCC.

Methods

This single-center, retrospective chart review included patients who were diagnosed with metastatic RCC and were prescribed a TKI at the Georgia Cancer Center-Laney Walker campus between January 1, 2015, and June 30, 2020. Eligibility criteria were age ≥18 years, a diagnosis of metastatic RCC, and being prescribed a TKI, either sunitinib, pazopanib, cabozantinib, lenvatinib plus everolimus, everolimus, or axitinib. Patients were excluded if they received adjuvant sunitinib or a TKI plus an immune checkpoint inhibitor.

The study protocol was reviewed by Augusta University’s Institutional Review Board and was determined to be exempt from Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations, and a waiver of HIPAA authorization was issued.

The study patients were identified via the Georgia Cancer Center-Laney Walker Campus’ electronic prescription orders and the specialty pharmacy dispensing records. Patients’ electronic records were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria before the data collection and analysis. The study data were collected and managed using the REDCap electronic data capture tool, a secure web-based software platform that is designed to support data capture for research studies, and is hosted at the University of Georgia.15,16

The data collected include patients’ baseline demographics; receipt of an immune checkpoint inhibitor before or after a TKI use; the TKI’s line of therapy, the drug’s name, initial dose, and start date; and date and reasoning for dose reduction, temporary treatment interruption, and/or treatment discontinuation date, when applicable. For each patient in the study, we calculated the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) criteria score,17,18 the Child-Pugh score, and creatinine clearance (CrCl) based on the patient’s height, weight, and laboratory values obtained on the date of the prescription for the first-line TKI.

In the IMDC criteria score, the prognostic factors represent a period of less than 1 year from diagnosis to the use of systemic therapy; a Karnofsky performance status score of <80%; a hemoglobin level of less than the lower limit of normal; and a corrected calcium, a neutrophil count, and a platelet count of more than the upper limit of normal. The favorable risk category has none of these prognostic factors, the intermediate risk category has 1 or 2 of these prognostic factors, and the poor risk category has 3 to 6 of these prognostic factors.17,18 We considered these categories in our patients.

Corrected calcium was used if the albumin level was <4 g/dL. If no laboratory values were documented from the date of the TKI prescribing, values obtained closest to the date of the first prescription were used (≤2 months from date of first-line TKI prescription). If a data item was required for the IMDC criteria, CrCl calculation, or the Child-Pugh score was missing from a patient’s medical record, then the result was inputted as “not reported.”

Reduced TKI dosing was defined as a decrease in the dose or frequency, or a dosing schedule different from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indication of the drug. Patients were considered lost to follow-up if they were not documented in the patient’s electronic record and if the patient’s record did not include a death certificate.

The primary objectives of this study were to evaluate how many patients received a first-line reduced starting dose of a TKI for the treatment of metastatic RCC and to compare patients who received a first-line starting dose of a TKI according to the FDA-indicated amount (ie, a full dose) and those whose dose was lower than the FDA-indicated dose (ie, a reduced dose).

The secondary study outcomes included the impact of a reduced starting dose of a TKI on the duration of therapy, the incidence of further dose reductions or interruptions, and overall survival, as well as the frequency of adverse events and/or the number of adverse events leading to an intervention. The patients who received a second- or third-line TKI for metastatic RCC were evaluated descriptively for the secondary outcomes.

Patients who received a second- or third-line TKI for metastatic RCC were evaluated separately. For these patients, descriptive statistics were used to report how many patients received a reduced starting dose for that line of therapy. In addition, using a descriptive report, we compared patients with reduced versus full dose for the incidence of additional dose reductions or interruptions, as well as the number of adverse events leading to an intervention.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc; Cary, NC), and statistical significance was assessed using an alpha level of 0.05. The prevalence and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the reduced dosing of the first, second, and third lines of TKI treatment were determined.

We calculated descriptive statistics within the first-line reduced TKI dosing and used a chi-square test or two-sample t-test to compare patients with reduced dosing versus patients with full dosing. If there were violations to the assumptions for the chi-square test or two-sample t-test, a Fisher’s exact test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed. A Kaplan-Meier survival curve with a log-rank test was used to examine the differences in mortality between patients who received a first-line reduced-dose TKI and those who received a full-dose TKI.

Finally, we examined the differences between the first-line reduced-dose and full-dose groups for further dose reduction, dose interruption, or treatment discontinuation; the duration of treatment interruption; and the duration of treatment until discontinuation within patients with a further dose reduction, those with dose interruption, or those with treatment discontinuation, which were determined using a nonparametric Fisher’s exact test or a Wilcoxon rank-sum test, because of the small sample size in these subgroups.

Results

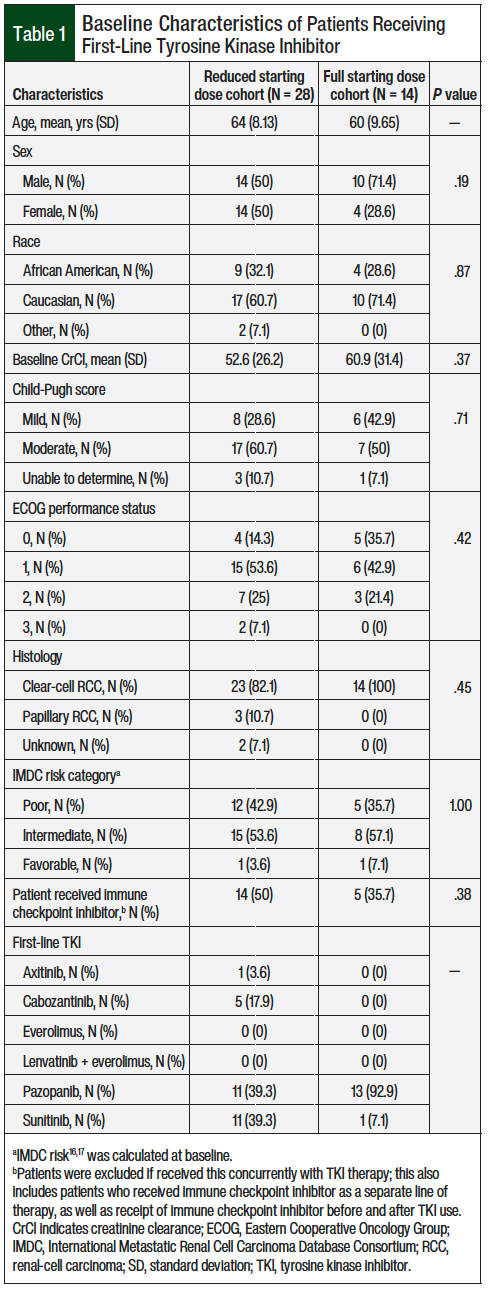

We reviewed a total of 63 patient charts, and 42 patients met the study’s inclusion criteria. The patients’ baseline characteristics were similar between the full-dose and the reduced-dose groups, with a majority of patients having an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of 0 or 1 and an intermediate IMDC risk (Table 1).

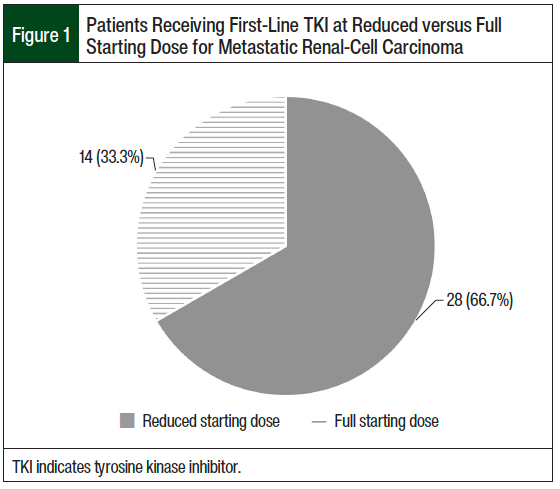

A total of 28 (66.7%) patients who received first-line therapy had an initial dose reduction of the TKI, and 14 (33.3%) patients received the full FDA-indicated starting dose of the TKI (Figure 1). There were no statistical differences in any secondary outcomes between patients who were initiated treatment with a reduced-dose TKI and those who were initiated treatment with a full-dose TKI.

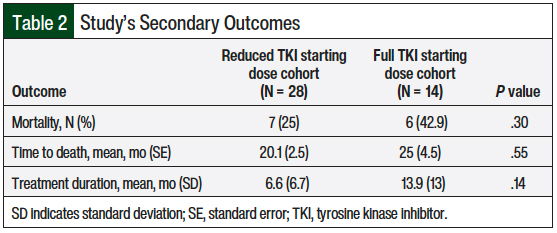

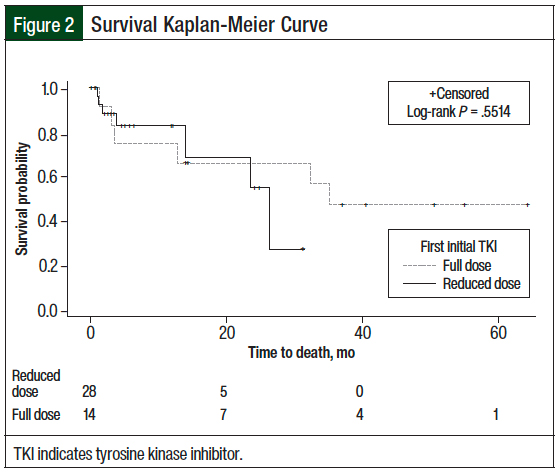

A total of 7 (25%) patients who received the reduced starting TKI dose died compared with 6 (42.9%) patients who received a full starting dose of TKI (P = .3; Table 2). Although mortality was not statistically different between the 2 groups, the difference was clinically different. Because 50% of the patients in each of the 2 groups did not die, the median survival and upper limit of 95% CI could not be estimated. The mean time to death in patients who received the reduced starting TKI dose compared with those who received a full starting TKI dose was 20.1 months versus 25 months, respectively (standard error, 2.5 months vs 4.5 months, respectively; P = .55; Figure 2).

Of note, 22 (78.5%) patients who received a reduced starting dose were prescribed it in 2017 or later compared with all 14 (100%) of those who received a full starting dose that was prescribed in 2017 or earlier. Therefore, the mean treatment duration of the 2 groups was 6.6 months versus 13.9 months, respectively (P = .14; Table 2).

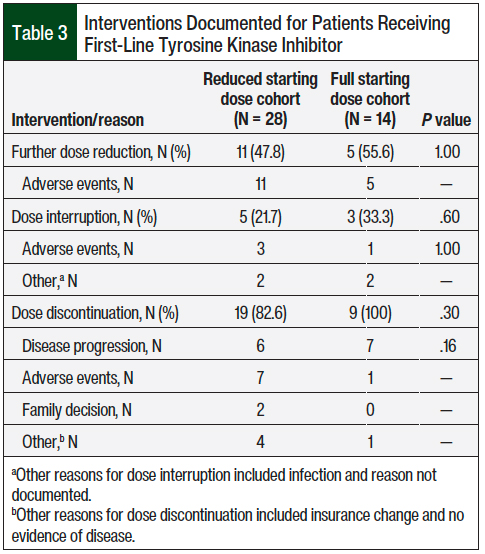

Among the patients who received a first-line TKI, many required at least 1 intervention, such as a dose reduction, dose interruption, or treatment discontinuation. Specifically, further dose reductions were observed in 11 (47.8%) patients who received a reduced starting dose compared with 5 (55.6%) of those who received a full starting dose (P = 1), whereas dose discontinuations were observed in 19 (82.6%) patients who received a reduced starting dose versus 9 (100%) of those who received a full starting dose (P = .3; Table 3). In the full- and reduced-dose cohorts, the most common indication for dose reduction was adverse events (100% for both cohorts); for dose discontinuation the indications were adverse events (36.8% and 11.1%, respectively) and disease progression (31.6% and 77.8%, respectively; Table 3).

Outcomes for patients who received second- and third-line TKIs were reported descriptively. A total of 16 patients received a second-line TKI; of those, 14 (87.5%) were prescribed a reduced starting dose and 2 (12.5%) were prescribed a full starting dose. In these patients, among those who received the starting dose of second-line TKI, 4 (28.6%) patients had further dose reductions and 9 (64.3%) patients had further dose discontinuations compared with 2 (100%) patients and 1 (100%) patient who received the full starting dose of second-line TKI.

Adverse events and disease progression were the most common reasons for interventions related to second-line therapies. Of the 9 patients who received a third-line TKI, 7 (77.7%) received a reduced starting dose and 2 (22.2%) received a full starting dose. Further dose reductions and treatment discontinuations were observed in 3 (42.9%) and 4 (57.1%) of the patients who received a reduced dose of third-line TKI compared with 1 (50%) and 1 (50%) of the patients who received a full dose of third-line TKI, respectively. Again, adverse events and disease progression were the most common reasons for interventions related to use of third-line therapy.

Discussion

Anti-VEGF TKIs are the mainstay of treatment for patients with metastatic RCC. Many of these agents, however, have an extensive side-effect profile that often leads to dose adjustments or treatment discontinuation. To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to review the impact of reducing the initial starting dose of TKIs in patients with metastatic RCC. Previously, most studies assessed dose reductions after patients had adverse events.2,5,10-12 In addition, various TKIs were evaluated in our study to account for the many therapy options available to patients.

Our study revealed that the majority of current patients at our institution are being started with a reduced dose of a TKI for the treatment of metastatic RCC. No differences were observed in overall survival or in the number of patients with dose reductions or treatment discontinuations between those who were started with a reduced-dose TKI and those who were started with a full-dose TKI. Similar to most previous reports,2,5,10-14 the lack of deleterious effect on patients’ outcomes further supports the use of an initial reduced-dose TKI strategy.

Previous studies have reported the successful reduction of TKI dosing after patients were intolerant of treatment with a TKI.2,5,10-12 Iacovelli and colleagues evaluated the clinical outcomes of patients with metastatic RCC who were intolerant of a standard-dose TKI and subsequently received a reduced dose of sunitinib (37.5 mg on a 4-week on, 2-week off [4/2] schedule, then 25 mg on that same schedule) or pazopanib (600 mg daily, then 400 mg daily) and compared the outcomes with patients who continued to receive the standard dose of sunitinib or pazopanib. The median overall survival in the patients who continued treatment with a standard-dose TKI was 24 months compared with 49.4 months in the patients who received a reduced-dose TKI (hazard ratio, 1.8; P <.001).5

Furthermore, these studies have demonstrated improved tolerability and clinical outcomes with a switch from sunitinib on a 4/2 schedule to a modified (reduced) schedule of 2 weeks on and 1 week off (2/1).2,10-12

In the RAINBOW analysis, patients starting with the 4/2 dosing schedule who then transitioned to the 2/1 dosing schedule had a median overall treatment duration of 28.2 months and a median progression-free survival of 30.2 months.2 Najjar and colleagues retrospectively assessed patients who started treatment at a 4/2 dosing schedule and over time transitioned to the 2/1 dosing schedule.10 The overall median progression-free survival was 43.9 months.10

In addition, Atkinson and colleagues assessed patients who transitioned from the 4/2 dosing schedule to an alternative dosing schedule.11 In this study, the median progression-free survival was 9 months with the 4/2 dosing versus 14.5 months with alternative dosing (P <.0001).11 Bjarnason and colleagues assessed patients receiving treatment with sunitinib on the 4/2 schedule, as well as those receiving the reduced doses of 37.5 mg or 25 mg, with an individualized schedule.12 The median progression-free survival was 12.5 months, and the median overall survival was 38.5 months.12 These studies demonstrated the association of dose reductions in patients who received pazopanib or sunitinib with reduced toxicity, without affecting survival.

Minimal data are available for initial empiric dose reduction (ie, before treatment-related adverse events while receiving a standard-dose TKI therapy) in patients with metastatic RCC. Specifically, only a few studies have evaluated empiric alternative dosing strategies for sunitinib in patients with metastatic RCC with the goal of balancing the least amount of drug exposure with efficacy to improve overall tolerability.2,13,14,19

In the RAINBOW analysis, patients who empirically started treatment with sunitinib on the 2/1 dosing schedule had a median treatment duration of 7.8 months and a median progression-free survival of 10.4 months compared with 9.7 months and 9.7 months, respectively, in the external controls who received an initial full dose of sunitinib.2 The small sample size and evaluation of only 1 TKI agent limits the interpretation and applicability of the study’s results.2

In addition, 2 phase 2 studies evaluated the safety and efficacy of continuous treatment with sunitinib at a lower dose (37.5 mg daily) than is recommended by the FDA in patients with metastatic RCC who are TKI-naïve13,14; however, these studies reported conflicting conclusions. In the study by Motzer and colleagues, sunitinib 37.5-mg continuous daily dosing was compared with the standard 50-mg 4/2 dosing schedule and showed no significant difference in overall survival (23.5 months vs 23.1 months, respectively; P = .615) or frequently reported adverse events.13 These results led the study investigators to recommend continued adherence to the FDA-approved standard of 50-mg sunitinib on a 4/2 dosing schedule.13

By contrast, Barrios and colleagues found a shorter median progression-free survival (9 months vs 11 months, respectively) and similar rates of treatment-related adverse events with continuous 37.5-mg dosing of sunitinib compared with 50 mg on a 4/2 dosing schedule used in the pivotal phase 3 clinical trial.14,20 The investigators concluded that the standard intermittent dosing of sunitinib may be optimal, but that the continuous once-daily dosing of sunitinib could be an alternative first-line treatment for metastatic RCC in select patients.14

A single-center, retrospective analysis evaluated the differences in efficacy and safety between standard-dose (60 mg daily) cabozantinib and empirically reduced-dose (40 mg daily) cabozantinib as second-line or later therapy in patients with metastatic RCC.19 The study team reported median progression-free survival of 5.9 months and 8.3 months, respectively, and overall survival rates of 44% and 54%, respectively, with the standard and reduced doses of cabozantinib; however, to date, this report has only been published in abstract form.19

Our study findings support the conclusions of these previous reports and address the limitations of previous studies that focused on single agents and/or first-line setting only.2,5,10-14

Limitations

Our study has several limitations, including the small sample size and its retrospective design. In addition, 5 (12%) patients continued therapy beyond the cutoff date for our data collection; therefore, the survival data are not mature at this time.

Notably, although all the patients included in this study received a TKI between January 2015 and June 2020, the prescribing patterns changed during that period. In 2017 and earlier, all 14 (100%) patients were prescribed a full dose of a TKI, whereas from 2017, 22 (78.5%) patients were prescribed a reduced starting dose.

Furthermore, the majority of the TKIs for patients with metastatic RCC were prescribed by the same provider, who changed the prescribing practice to an initial reduced dose based on clinical experience over several years with patients using an initial full dose. Ultimately, this could have influenced the patients’ outcomes, such as treatment duration and time to death.

Finally, specific dose adjustments that resulted from drug interactions were not documented in our medical records, which could have influenced the number of, and reason for, the initial TKI dose reductions.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that starting a TKI at a reduced dose improves medication tolerability, without compromising its efficacy. Furthermore, more patients with metastatic RCC started treatment with a reduced dose of a TKI than patients who started with the full FDA-approved dose, with no differences in survival or requirement for further dosing interventions. Larger prospective studies are needed to determine if initiating TKIs at a reduced dose in patients with metastatic RCC can improve tolerability without compromising efficacy.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr Stitt, Dr Saunders, Ms Rowling, Dr Waller, and Dr Clemmons have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Kidney Cancer. Version 4.2022. December 21, 2021. www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/kidney.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2022.

- Bracarda S, Iacovelli R, Boni L, et al; for the RAINBOW group. Sunitinib administered on 2/1 schedule in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: the RAINBOW analysis. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2107-2113. Erratum in: Ann Oncol. 2016;27:366.

- Ravaud A. How to optimise treatment compliance in metastatic renal cell carcinoma with targeted agents. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(suppl 1):i7-i12.

- Tenold M, Ravi P, Kumar M, at al. Current approaches to the treatment of advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2020;40:187-196.

- Iacovelli R, Cossu Rocca M, Galli L, et al. Clinical outcome of patients who reduced sunitinib or pazopanib during first-line treatment for advanced kidney cancer. Urol Oncol. 2017;35:541.e7-541.e13.

- Fujita KI, Ishida H, Kubota Y, Sasaki Y. Toxicities of receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer pharmacotherapy: management with clinical pharmacology. Curr Drug Metab. 2017;18:186-198.

- Osawa H. Response to regorafenib at an initial dose of 120 mg as salvage therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;6:365-372.

- Reiss KA, Yu S, Mamtani R, et al. Starting dose of sorafenib for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective, multi-institutional study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3575-3581.

- Miao E, Seetharamu N, Sullivan K, et al. Impact of tyrosine kinase inhibitor starting dose on outcomes in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Pharm Pract. 2021;34:11-16. Epub ahead of print June 5, 2019.

- Najjar YG, Mittal K, Elson P, et al. A 2 weeks on and 1 week off schedule of sunitinib is associated with decreased toxicity in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:1084-1089.

- Atkinson BJ, Kalra S, Wang X, et al. Clinical outcomes for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with alternative sunitinib schedules. J Urol. 2014;191:611-618.

- Bjarnason GA, Knox JJ, Kollmannsberger CK, et al. The efficacy and safety of sunitinib given on an individualised schedule as first-line therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a phase 2 clinical trial. Eur J Cancer. 2019;108:69-77.

- Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Olsen MR, et al. Randomized phase II trial of sunitinib on an intermittent versus continuous dosing schedule as first-line therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1371-1377.

- Barrios CH, Hernandez-Barajas D, Brown MP, et al. Phase II trial of continuous once-daily dosing of sunitinib as first-line treatment in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cancer. 2012;118:1252-1259.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, at al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al; for the REDCap Consortium. The REDCap Consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208.

- Heng DYC, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor–targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5794-5799.

- Heng DYC, Xie W, Regan MM, et al. External validation and comparison with other models of the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic model: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:141-148.

- Grannan E, et al. Safety and efficacy of a lower starting dose of cabozantinib in renal cell carcinoma. Presented at HOPA Ahead; April 3-6, 2019; Fort Worth, TX.

- Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115-124.